Elizabeth Woodville was born in 1437 into a house of solid supporters of Lancaster. Her first husband lost his life fighting for his king at the second battle of St Albans and left his 23-year-old wife a widow with two young sons aged six and five.

Disastrously for Elizabeth, her mother-in-law refused to pay her dower from the family estate at Groby, in Leicestershire, leaving the widow penniless. Only the king himself would be able to enforce her rights, and he was the handsome Edward IV of York, the enemy of her house.

Elizabeth managed to meet Edward as he was recruiting forces in the neighbourhood. In an account that sounds like a fairy story, but was current at the time, she waited for him, under an oak tree, and they immediately fell in love. They were married within weeks, and the young handsome king of the House of York was creeping nightly into a staunchly Lancastrian family house to be with his bride.

When Edward announced the marriage to his court it caused uproar. Elizabeth was a commoner – the first to take the giant leap upwards to marry royalty – she was a Lancastrian, she had a dozen brothers and sisters who would have to be found wealthy partners and titles. But worse than all of this: within days there were rumours of seduction and even outright witchcraft to explain the king’s behaviour.

Her greatest enemy was the king’s mentor – the man who had put him on the throne. Richard Neville Earl of Warwick could not tolerate Elizabeth’s influence over his young cousin and within five years had chosen a new protege – Edward’s own brother George Duke of Clarence.

Catching the king by surprise, Warwick captured Edward and then pursued his hated rivals. He beheaded Elizabeth’s father and brother, and put her mother on trial for witchcraft. Elizabeth held her nerve, and her young husband held his. Warwick could not force Edward to agree to anything and finally set him free. Jacquetta was released unhurt but she and her daughter were left with a shadow over their reputation that not even a public acquittal could remove.

The uneasy peace between the kingmaker and the king that he had made could not last. Warwick masterminded another rebellion with the exiled queen of Lancaster, Margaret of Anjou. Edward had to escape into exile, leaving Elizabeth unprotected and pregnant with her fourth child.

Bravely, Elizabeth went into sanctuary and gave birth in the crypt of a church near to Westminster Abbey while, almost over her head, the Lancastrian king Henry VI was crowned again. Her baby was a boy and Edward, with a dynasty to establish, marched home, reunited with his brother George, and recaptured the throne.

It should have been a time of peace, but Edward’s brother George hated Elizabeth, and started rumours that she was a witch, even printing pamphlets accusing her of bewitching his brother. He claimed that she was a poisoner, and took his pregnant wife Isabel Neville away from court. When Isabel died George claimed that she had been poisoned by the witch-queen.

Edward arrested George and his fellow-conspirators, and had them put to death, but the shadow of witchcraft would damage Elizabeth’s reputation again when, on the death of her husband Edward, his surviving brother Richard seized the throne, accusing her of having bewitched his brother into a bigamous marriage. Elizabeth’s marriage was declared invalid, and her two sons were taken into the Tower of London by their uncle Richard III, and disappeared.

Elizabeth went into sanctuary with her daughters and, from there, found the courage and energy to mastermind plots against the new usurping king. She conspired with her former lady-in-waiting Margaret Beaufort and launched an attack on the Tower to free her sons. When that failed, and the rumours started that the boys had disappeared, she betrothed her daughter Elizabeth to Margaret’s son Henry Tudor, and when Henry won the Battle of Bosworth she saw her daughter take the throne beside the Tudor king.

Even towards the end of her life, with her daughter on the throne and her grandson as Prince of Wales, Elizabeth may have plotted against Henry Tudor. She was sent to live in Bermondsey Abbey with only occasional visits to court, and her lands were transferred to her daughter. This coincided with the Simnel rebellion, and it may well be that Henry suspected her of conspiring with the rebels. She died there, with very little fortune for a dowager queen, but with the satisfaction of having fought and won her throne, and founded a dynasty.

With this marriage my Elizabeth will become Lady Grey of Groby, mistress of a good part of Leicestershire, owner of Groby Hall and the other great properties in the Grey family, kinswoman to all the Greys. It is a good family, with good prospects for her, and they are solidly for the king and fiercely opposed to Richard Duke of York, so we will never find her on the wrong side if the dispute between the Duke of York and his rival, the Duke of Somerset, grows worse.

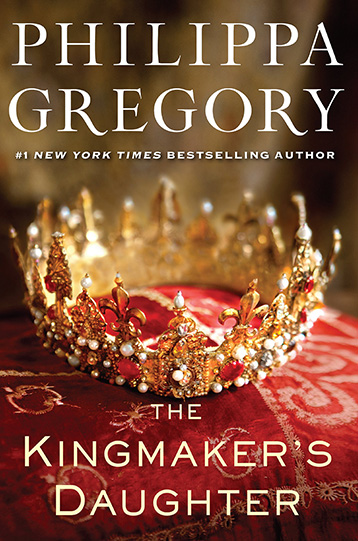

From The Red Queen

I have some nights of worry that I will disgust him by being so blunt about my plans. Then I think of Elizabeth Woodville waiting for the King of England under an oak tree, as if she just happened to be by the roadside, a hedge-witch casting her spells, and I think that my way at least is an honourable offer and not a begging for an amorous glance and a sluttish strutting of her well-worn wares.

From The White Queen

‘But now I have to go north and deal with this,’ Edward complains to me. ‘There are new rebellions coming up like springs in a flood. I thought it was one discontented squire but the whole of the north seems to be taking up arms again. It is Warwick, it must be Warwick, though he has said not a word to me. But I asked him to come to me; and he has not come. I thought that was odd – but I knew he was angry with me – and now this very day I hear that he and George have taken ship. They have gone to Calais together. God damn them, Elizabeth, I have been a trusting fool. Warwick has fled from England, George with him, they have gone to the strongest English garrison, they are inseparable, and all the men who say they are out for Robin of Redesdale are really paid servants of George or Warwick.’

I am aghast. Suddenly the kingdom which had seemed quiet in our hands is falling apart.

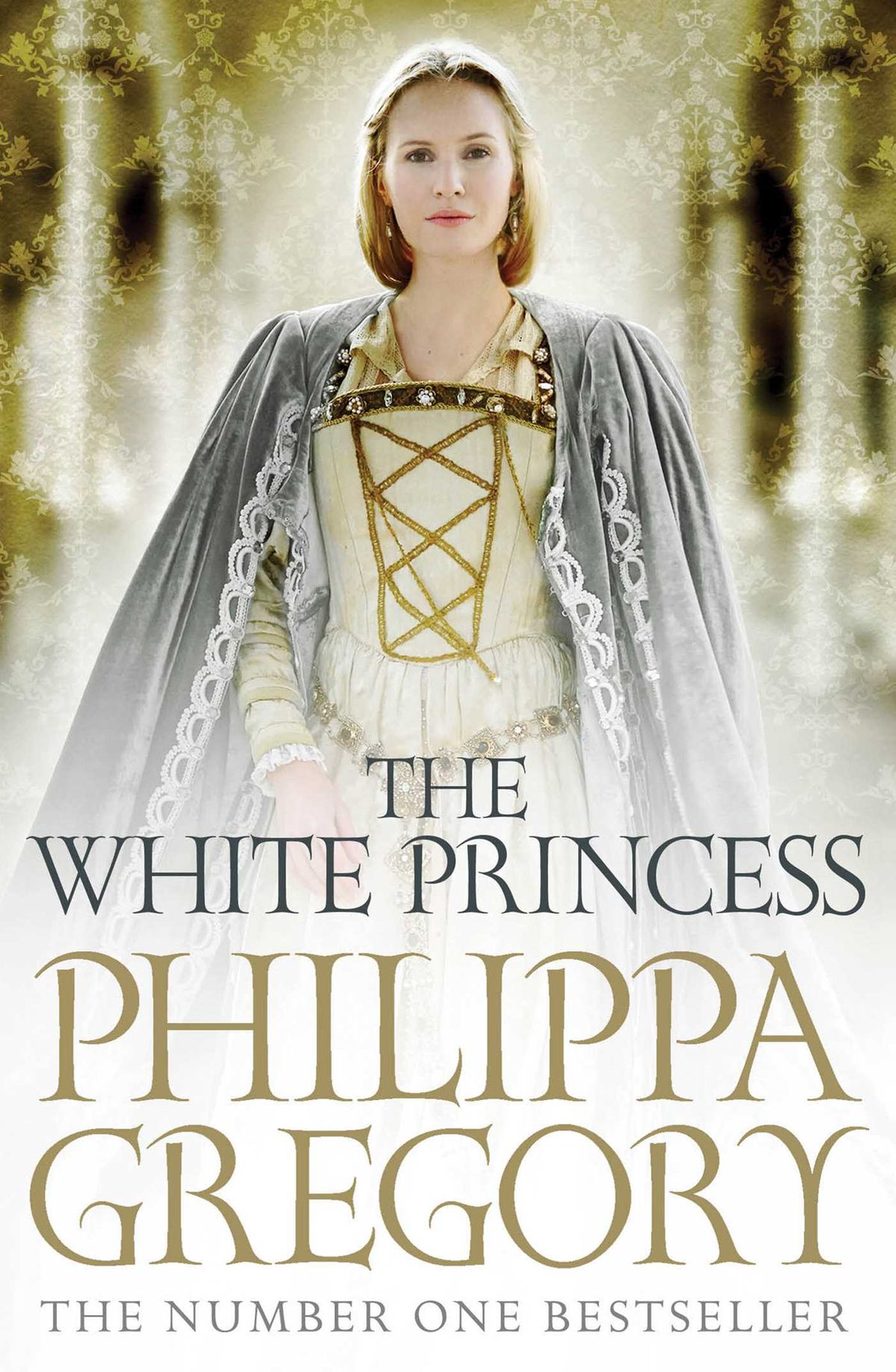

From The White Princess

And then, suddenly, as if by magic, I see her. There is a standard, uncurling and flapping in the breeze from the river. It is Tudor green, the new colour of loyalty, Tudor green background embroidered with the Tudor rose of white and red, as every sensible person would show today. But this flag is different: it’s a white rose on the Tudor green and if there is a red centre to the rose it is stitched so small that it cannot be seen. At first glance, at closer glance, this is the white rose of York. And there, of course, is my mother standing under the standard of the husband she adored, and as I look towards her and raise my hand, she gives a girlish jump of joy that I have seen her and she waves both her hands above her head, shouting my name, exuberant, laughing, rebellious as ever. She starts to run along the riverbank, keeping pace with my distant barge, shouting, ‘Elizabeth! Elizabeth! Hurrah!’ so clearly that I can hear her over the noise across the water. I rise up from my solemn throne, rush to the side of the boat and lean out to wave back at her, quite without any dignity, and shout, ‘Lady Mother! Here I am!’ and laugh aloud in delight that I have seen her, and that she has seen me, and that I am going to my coronation with her laughing easy blessing.

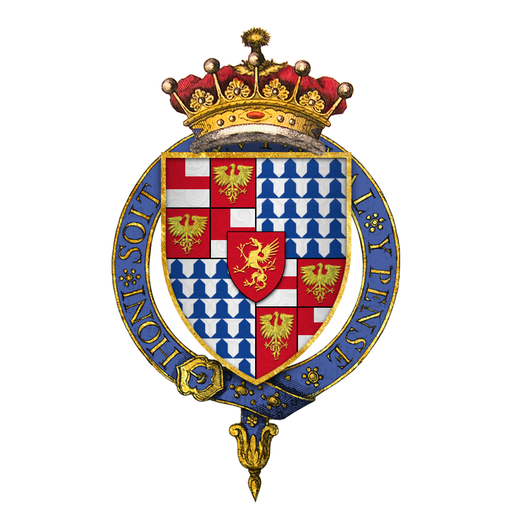

Image: Elizabeth Woodville (1437?–1492) by unknown artist, British School, c.1550–1600, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014, RCIN 404744